ex dono auctoris – En gave fra forfatteren

Coakley om Thomas’ fem veier

- The argument from motion is untenable in a post-einsteinan age

- The argument from efficient causation

- In the case of humans we are familiar with the idea that human ‘propel’ themselves. They are autonomous.

- In relation to non-human entities we can now say that the evolution theory deals with causal nexuses in the non-human world.

- The argument rom the idea of ultimate neccesity

- It is question begging. Only someone who already looks for the idea of a God feels the need to ask for a primal necessity

- The beauty and the affection of natural world suggests a gradation with an ultimate ontological source

- It’s only convincing if you are a platonist.

- The teleological argument

- This also not needed if we don’t presume the need of a ultimate course. With Kant, we can account for the directness of the world by the directness of ourselves. We see teleology, because we add it in seeing.

- This interesting! For what should these thomistic arguments do? Shall it force you into belief? Or can we say that they already have had an effect on Kenny?

- Return to a thomist view of relation between reason and faith is where the way forwards lies. Swinburne’s attempt doesn’t work, because it presupposes no faith at all. But the other view abandons apologetics totally.

- About Denys Turner’s book:

-

- He wants to defend the statements of the 1 Vatican council. But then he does some quick footwork, as he argues that because of the apophatic has to be balanced with the kataphascisim, we have to reexamine the very nature of reason. That reason when working according to the light of faith, is always in a process of transformation.

- This blurs the line between reason and faith, though it is a diachronic blurring.

- It can attempt to start with secular science and reason. At the best it will end up with an probabilistic approach.

- It can use argument to bolster up faith. But faith precedes reason. (McCabe, Gilson etc)

- It can explore the tensions between rational argumentation and apophatic response. By considering whether reason itself must be reconstrued. Without throwing out rational demonstration (Turner)

- It can argue that as a very important demand of giving an account of the faith that is in them, one has a duty to set out arguments as clear as possible for people outside the church as well as within the church. With a clear understanding that it will never go all the way, but they can lead you to a point where you have to decide: Go to church or not? (Coakley)

Fremtiden

Det er litt mye som skjer for tiden, så det har blitt sparsomt med blogginnlegg. Men nå kan jeg i alle fall melde at jeg har fått plass på PhD her! Plassen er betinget på at jeg får en viss karakter på masteren min. Men veilederen min sa at jeg sannsynligvis kom til å gå veldig greit.

Da blir det altså 3-4 nye år her.

Å ikke finne løsningen

I går kveld hadde vi første møte med lesegruppen hvor vi leser Merleau-Ponty. De fleste der var PhD-studenter. Det var den mest sofistikerte samtalen jeg kan huske å ha vært med på. I den grad jeg var med på samtalen. Jeg kjente i de fleste der, men det var ikke alle jeg hadde vært i dyp teologisk diskusjon med. Flere av dem hadde en enorm kjennskap til filosofihistorien (Med detaljkunnskap om før-sokratiske filosofer!) og teologihistorien. Jeg følte meg dum. Men det var også veldig lærerikt!

Midt i samtalen satt vi litt fast da vi forsøkte å reflektere teologisk i dialog med M-P. En spurte: “Men hva er løsningen her?” Da svarte en annen: “Løsningen? Vi reflekterer ikke teologisk hvis vi leter etter løsningen.”

Noe å tenke på.

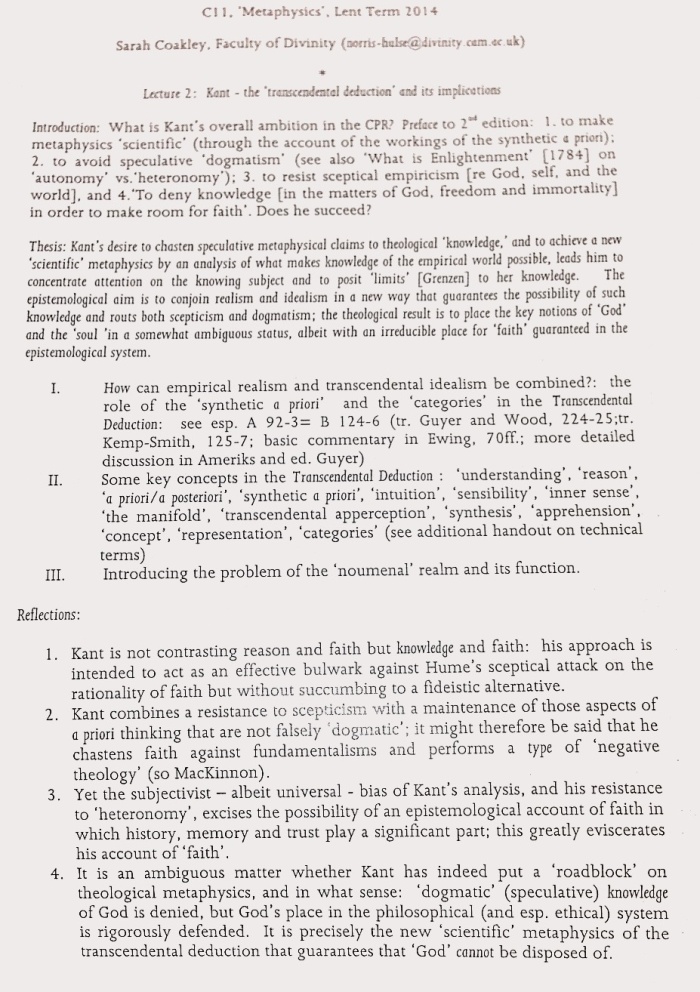

Coakley: Metaphysics 2

The copernican revolution: Acheiving a form of certainty which has all the desirable qualities of being a priori, but at the same time the qualities of being true of an outside world that is coming in.

Introduction: What is Kant’s overall ambition in the CPR? Preface to 2nd edition:

- To make metaphysics ‘scientific’ (through the account of the workings of the synthetic a priori)

- To avoid speculative ‘dogmatism’

- To resist sceptical empiricism (re God, self and the world)

- To deny knowledge [in the matters of God, freedom and immortality] in order to make room for faith.

- We must rethink God, freedom etc in terms of the postulates of practical reason. When we understand how we have knowledge of empirical reality, we will se that we cannot know God, freedom and the soul, but we need them. They have the role of being regulative ideas.

- Faith is not subjective of feeling-oriented. It is truly a rational undertaking.

- Skepticism is left out, room for God etc found

- Leaves out dogmatism (including church authority)

- This is of major importance for Kant.

- He has made the individual subject the decider of the position of God. And the position of God has been made secondary to epistemological concerns. Secularization of reason.

- Ecclesiastical and revelatory authority has been marginalized!

- The role of the ‘synthetic a priori’ and the ‘categories’ in the Transcendental Deduction

- Newton: Space is out there

- Leibniz: Space and time are conceptual constructs

- If it is the former, then knowledge can never be a priori

-

- Problem: Then knowledge is not universal and certain

- If it is the latter

-

- The, since the representation does not produce its object as far as its existence is concerned, the representation is still determinant of the object a priori if it is possible through it alone to cognize something as an object.

- Of Quantity

- Of Quality

- Of Relation

- Of Modality

- Sense: Receive the stuff

- Imagination: The mediating role: It is the bridge between sense and the application of the categories.

- Apperception: How the mind is able to unify everything that is coming in. Here there is a ‘meness’, which is saying that I am having these experiences, not you. Almost a mysterious unifying capacity of the soul

Kremt.

Jeg hadde et innfall for noen dager siden. Innfallet fikk meg til å smile da jeg forsto at det hele var en meget ironisk situasjon. Situasjonen jeg snakker om er da jeg kom inn på biblioteket om morgenen. Over skulderen hang veska med macen min, og i hendene mine hadde jeg sju eller åtte bøker med teologisk litteratur. Nå falt øynene mine på en bok om den Hellige Ånd. Denne boken ga meg følgende innfall: Hadde det ikke vært kjekt å lese noe skikkelig teologi en gang?

Ironien, og derav smilet, kom selvsagt av at jeg ikke gjør stort annet enn å lese teologi. Men samtidig – og dette ga ironien en bismak – var dette mer enn et intellektuelt begjær. Det var ikke først og fremst denne lysten om å lese det du ikke leser akkurat nå; å ha det du ikke har. Ikke at jeg er fremmed for dette begjæret. Men nå handlet det om noe annet. Det var lysten etter å snakke om, i stedet for å snakke om å snakke om.

Jeg vet ikke om det finnes en diagnose for dette jeg førsøker å nærme meg her. Om jeg selv kan få besteme navnet på diagnosen, vil jeg både inkludere ordet ‘meta’ og ha en eller annen etymologisk kobling til Descartes.

Et annet symptom kom til syne forrige onsdag. Jeg satt i et seminar med en rekke velartikulerte og oppegående mennesker. Vi skulle studere Exodus 3. Moses, busken og navnet. Seminarserien handler om teologisk hermeneutikk. Målet for seminaret var å eksegere teksten teologisk, ikke først og fremst å snakke om metode. Resultatet ble jo selvsagt lesninger på mange forskjellige nivåer; overlappende, komplementære og motstridende måter å lese teksten på. Det føltes skittent. Jeg var utilpass. Som om vi snakket når vi burde ha vært stille. Et seminar om teologisk hermeneutikk? No problem! Et seminar hvor vi eksegerer? No way!

Jeg innrømmer det: Nyhetsverdien i denne bloggposten er riktignok ganske lav. Dette er slett ikke noe annet enn det enhver teologistudent føler i en bibelgruppe: Et tap av uskyldighet. Troath-clearing: Harkingen overtar: “Kremt. Det er jo klart at de fleste forskere vil nok ikke…” Men ikke misforstå. Det er ikke bibelproblematikken i seg selv jeg forsøker å nærme meg her.

Det er heller denne hangen til metode, til meta-prat. Selv om jeg selv kan være et ekstremt tilfelle av denne diagnosen, er det ingen tvil om at dette er et utbredt fenomen i moderne teologi. Så utbredt at systematikker som skrives i dag (hvis de skrives) alltid begynner med en nedlatende refleksjon over hvordan prologomena ble lengre og lengre i tidlig-moderne teologi. Deretter følger enten en fullstendig avvisning av refleksjon om metode (av Barthiansk art), eller så har hele systematikken blitt omgjort til en metodisk refleksjon. En eneste lang hostekule som produserer lite annet enn slim.

Nå er jeg ikke ukjent med de idehistoriske betingelsene for denne situasjonen. De filosofiske teoriene som en gang produserte dette endeløse problemet med fundamenter, metode og prolegomena har i dag blitt syndebukkene; objekter for lite annet enn avvisning. Sånn sett er diagnosen kanskje heller av psykologisk art. Det er den patologiske tilstanden hvor man følelsesmessig er satt tilbake 300 år. Ennå ikke kommet lengre enn Descartes. Selv om man erkjennelsesteoretisk vet at sånn er det ikke.

For min egen del, da, handler det kanskje ikke om å bli enda flinkere på å snakke om å snakke, men heller å snakke. For å avslutte dette, så kommer jeg med fire forslag til unge post-moderne teologer med urovekkende diagnoser. Disse er ikke så mye teoretiske, som praktiske:

1. Teologien dør når vi slutter å snakke, fordi teologi er en samtale. Første lov må derfor være å fortsette samtalen.

2. Meta-diskurs er viktig for teologien. Teologi er i seg selv en andre ordens diskurs: Man prater om hva kirken bør si. Men faren er om teologi bare blir tredje ordens diskurs, altså bare prat om hva en teolog skal si. Det er forskjellen på om teologen skal skrive bøker om Den Hellige Ånd i ny og ne eller bare publisere metodikk. Andre forslag er derfor: Prat om Den Hellige Ånd. Og Gud. Og hva kirken skal si om dette og hin.

3. Ikke la deg stoppe av begrunnelsens snare. Vi vet jo at det er alltid nok et “hvorfor?” bak et “hvorfor?”. Det betyr ikke at teologien må være irrasjonell eller oppspinn. Men all diskurs må, hvis det i hele tatt skal være diskurs, ta noen ting for gitte.

4. Definer det gitte ut i fra dine desiderata. Anta det du ønsker ønsker at teologien skal forholde seg til og se hva som skjer. Ta for eksempel for oss sårede lutheranere og vår bibelbruk. Vi satset (nesten) alt på Bibelen og tapte. Og nå finner vi oss paradoksalt ute av stand til til å bruke den. Men om vi ønsker å fortsette den teologiske diskursen må vi fortsatt bruke Bibelen. Som om vi vet hvordan. Det handler ikke så mye om å fake det, som en magefølelse om det dette skal funke på en måte, selv om vi egentlig helt vet hvordan.

Dette er selvsagt ikke rettningslinjer for hvordan man skal ‘bedrive’ teologi. Tenk heller på det som piller på blå resept.

Forelesning om Schleiermacher 1

I dag hadde ei vennine av meg en forelesning om Schleiermacher. Vi var en gjeng postgraduates som stakk innom som moralsk støtte (og ikke minst for å lære!). Til tross for at det var hennes første forelesning noen sinne, og at vi feiret bursdagen hennes på en pub i går kveld (med … tilstrekkelig menge alkohol), var det en veldig god forelesning. Det var for det meste kontekst, siden det var første forelesning, men en del av dette er nytt for meg også. Det er bra å lære litt mer om Schleiermacher utenom fordommene vi har arvet gjennom Barth.

—

- Schleiermacher was too accommodating. Overemphasizing human reason, to the detriment of revelation.

- Neglected the gospel.

- The significance of a text cannot be reduced to its content, but must be situated in a context. The texts we read are entangled into a historical web of relationships.

- In the Napoleonic wars he thus expressed his patriotism

- Reformed Tradition (Calvinisim)

-

- Born into a family in the reformed tradition. His own father was a reformed chaplain in the Prussian army

- Pietism

-

- A protestant movement in the Lutheran tradition.

- Moral praxis and focus on Scripture rather than intellectual focus. Anti-hierarchical.

- The individualistic religiosity correlated with the individualism in general culture.

- But the ability to live a good Christian life comes from faith, not from reason.

- His schooling with the Moravian Brethren (Herrnhuter community (Jan Huuss)

-

- Roots in the 14th century.

- Universal education, liturgy in the language of the people, married priests.

- In the 17th century, they were persecuted by catholics and made to go under ground. They settled in Prussia in the mid 18th century.

- It was within the Marovian community that Schleiermacher was sent to begin his formal education. In a school for boys entering Christian ministry. They were ‘protected’ from the world outside. Pushed to dedicate themselves to a simple, devoted religious life, in communion with JC.

- None of the qualities connoted by feeling is worrying for theologians. If we understand faith as feeling, then faith becomes fideism.

- However, becoming familiar with his young crisis of faith may give us nuances.

- The sense that God was active in the world.

- A way of describing the process of secularization.